Fisheries Management and Economics: the urgency of a comprehensive data-based approach

Últimas noticias

A pioneering genetic catalogue reveals hidden biodiversity in Basque estuary sediments

Uhinak Technical Committee Sets the Key Points for the 7th International Congress on Climate Change and the Coast

“We fishermen are the ones who earn the least”

RAÚL PRELLEZO, researcher at Sustainable Fisheries Management

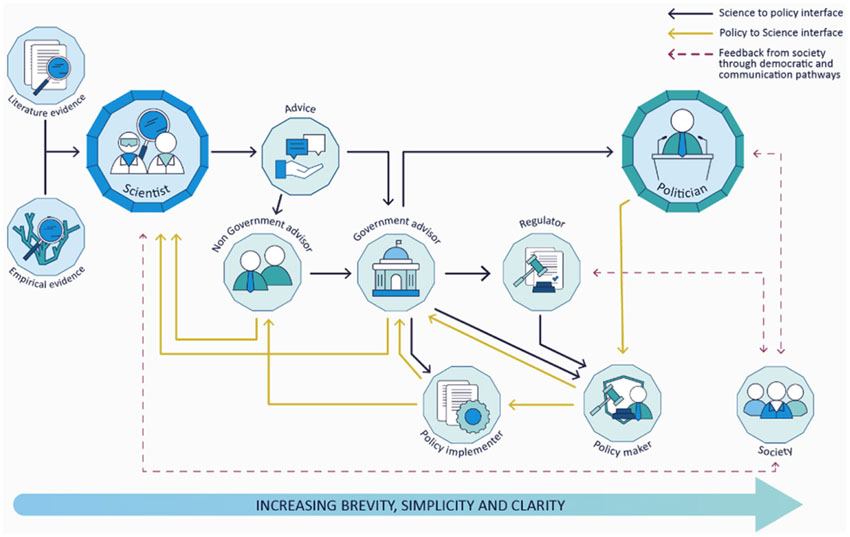

Fisheries management and economics are two areas that complement each other more than we think. In fact, economics should play a crucial role in fisheries management, as it is based on the paradigm of scarcity, of which fisheries is an example. And yet, the most important management measure in the Northwest Atlantic, the Total Allowable Catch (TAC), is not a direct indicator of this scarcity: it is a management measure based on specific targets, as stated in Article 2 of the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP). This objective is quantified by the maximum sustainable yield (MSY), which, although robust, should not be interpreted as a fixed point, but as a desired range, adaptive to different contexts.

MSY is not necessarily optimal from an economic perspective, but it moves the system in the right direction, that of sustainability. The debate on how to introduce economics into the context of fisheries management should not focus on whether the objective is appropriate, but on how to design an optimal policy to achieve it. This is where economics can offer fundamental guidance, integrating biological, financial and social dimensions to promote multidimensional sustainability.

A positive change in this regard is the recent update of the guidelines for balancing fishing capacity and fishing opportunities, which now emphasise equality between biological, economic and technical indicators. This suggests an evolution towards a more balanced approach, moving away from the ex-post or non-binding assessments that have dominated in the past.

Despite these advances, practical challenges remain, such as over-aggregation of data. For example, segmenting fleets by length and technology can obscure individual realities, complicating proper management advice. In addition, the ‘choke species’ phenomenon, in the framework of the landing obligation, highlights the need for clear economic criteria in management, to avoid very adverse consequences on fishing fleets.

The key is the effective use of existing data. While there will always be uncertainty in a variable natural environment, the value of data lies in their ability to inform ex-ante decisions, adjusted to clear and sustainable objectives. Economics does not provide absolute answers, but it does provide the best possible alternatives within current constraints.

Moving towards 3D fisheries sustainability – biological, economic and social – requires not only more data, but a paradigm shift in its application. This is the path towards integrated fisheries management, capable of securing resources for future generations.