Alternative proteins: relevance, benefits and barriers

Últimas noticias

Ocean Acidification in the Bay of Biscay: two decades of data confirm a rising trend

[EATrends] Nutrition4me: The Road to Precision Nutrition

Alternative Proteins: Opportunity, Innovation and the Future of the Food Industry

PAULA JAUREGI, Ikerbasque senior researcher working on Efficient and sustainable processes

CARLOS BALD, senior researcher working on Efficient and sustainable processes

The protein transition is a reality. Searching for and integrating alternative protein sources into our daily lives is a necessity that represents great opportunities but which, at the same time, faces great challenges. AZTI researchers Paula Jauregi and Carlos Bald describe some of the keys to face this great challenge for world food, with special emphasis on sustainability.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in so-called alternative proteins, which are unconventional in terms of their origin (new plant or animal species) or the processes by which they are obtained (physical, chemical or biotechnological).

Índice de contenidos

Why the interest in alternative proteins?

To ensure proper nutrition, 15-20% of energy intake should be in the form of protein.

Both animal and plant foods provide protein in our diets. However, in general, animal proteins are of higher quality, as they contain higher ratios of essential amino acids, those that the body is not able to synthesise. This does not mean that plant-based proteins are completely lacking in certain essential amino acids (most plant-based proteins will contain all 20 amino acids), but they tend to have a limited amount of some, known as their limiting amino acids. Consequently, in a plant-based diet, it is important to combine sources with complementary limiting amino acids.

Meat consumption continues to rise year on year, with demand increasing as people’s purchasing power increases. Moreover, Europeans generally consume more protein than we need, focusing on meat and unbalancing the diet to the detriment of other important nutrients such as dietary fibre, omega-6 fatty acids and other phytonutrients and vegetables and vitamins that constitute, among others, the basis of the Mediterranean diet.

It is estimated that by 2030 there will be 10 billion people to feed, which means a large amount of quality protein whose production needs to be diversified to be sustainable. In other words, we need to go beyond meat protein.

Against this backdrop, the protein transition is a reality that offers great opportunities for the food industry but also presents great challenges in terms of technology, regulation and education. But what exactly do we mean by alternative proteins?

Main alternative protein sources

Alternative proteins include macro-organisms such as insects, algae and new plant species, but special attention has also been given to single-cell protein production: microalgae, fungi (mycoprotein) and cultured meat, now called “cellular agriculture”.

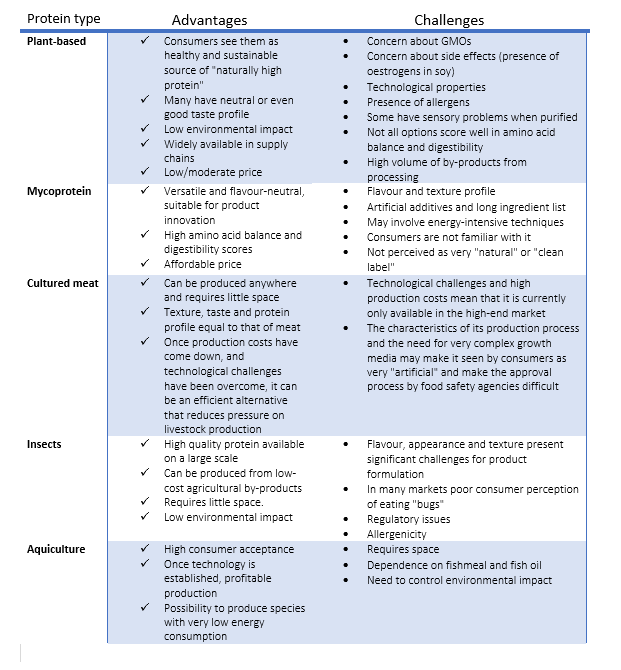

The following table shows the advantages and disadvantages of the different alternative protein sources:

Main obstacles for alternative proteins

Despite the growing interest in the protein transition and the fact that business ideas around alternative protein-based food production are continuously growing, there are many barriers.

First of all, in terms of regulation, initiatives and plans at European, state and even regional level that support sustainable protein production (Europe Green Deal, PEGA berra) often clash with legislation..

There are significant difficulties when including new sources of protein, especially when it comes to introducing new micro-organisms. At the same time, the procedure for obtaining authorisations to cultivate new species is often slow and causes potential producers to back out, as has happened, for example, with insects.

On the other hand, if we focus on sustainability, we cannot forget about resource consumption and carbon emissions. It is true that bioreactor-grown meat, veggie burgers and insects have less impact in terms of freshwater consumption and CO2 emissions than beef production, but if we make this comparison with other productions such as poultry and aquaculture, the advantages may not be so obvious.

There are also technological challenges. Being able to include alternative proteins in food formulations requires the use of technologies that enable appropriate sensory properties to be achieved. Otherwise, the need to include ingredients to improve consistency, mouthfeel, taste, stability, risks leading to labels with long lists of ingredients and additives. We must be imaginative in the design of products and recipes in order not to limit ourselves to “imitating” meat products but to offer innovative and attractive formats and forms of consumption.

An additional barrier is price, as the high cost of some alternative sources means that they are not an option for large-scale feeding and therefore cannot be considered as a solution to the food challenge. However, this barrier will be overcome as these new sources become standardised.

And last but not least, there is the disposition of consumers. Alternative proteins may be perceived as not as good as meat proteins (less “natural”), be rejected because of the origin of their ingredients, or be preconceived as less attractive in terms of taste or texture.

Thus, the key characteristics that products or recipes made with alternative proteins should meet could be summarised as follows: Accessible, Affordable and Attractive.

Conclusions

Alternative proteins solve different problems: the need of quality proteins for a good diet; reduction of the environmental footprint; or reduction of dependence on raw materials from abroad. And their development can offer considerable collateral benefits, such as increasing the production efficiency of certain industrial sectors.

For the production of alternative proteins to be efficient and have a truly positive impact, it will be necessary to focus on the circular economy, reducing the generation of waste and promoting local production.

And there are some other needs to be met. From the industry side, more efficient and environmentally friendly processing technologies for protein raw material sources need to be developed, without forgetting the need to improve the technological and sensory properties of the products.

On the institutional side, we need to promote a more flexible legal framework that facilitates the incorporation of new foods and, of course, there is an important educational task at a social level. Despite the fact that we have an increasingly aware population, there is still reticence towards certain products or ingredients that will have to be faced, because there is no point in a productive industry without receptive consumers. It is the responsibility of the food industry, scientific experts, technologists and nutritionists to inform society about what alternative proteins are, how they are obtained, how they are processed and what they provide us with and, most importantly, that a varied diet is the basis of a healthy and sustainable diet.

*This article was originally published in the October 2022 issue of TECNIFOOD magazine.